We Celebrated Our 25th Anniversary

February 7, 2019

The Birth of a Skipjack, Part III, the Building of the Nathan

March 11, 2019By Charles Rouse

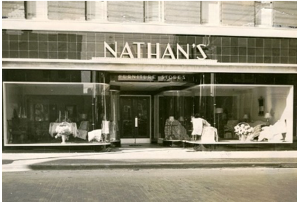

Around 1870, near the height of the oyster dredging industry, Meyer Nathan arrived in Cambridge, Maryland. Meyer travelled around the county as an itinerant tinkerer (one who fixed pots and pans), while 800 skipjacks travelled around the Choptank River and Chesapeake Bay fixated on dredging for oysters. Meyer Nathan was never a skipjack captain, and chances are he never set foot on a skipjack; yet he and his son, Milford, would, over a century later, have a profound influence on preserving the culture, history, and heritage of Maryland’s (Cambridge) skipjacks.

Meyer Nathan personifies an American ‘rags-to-riches’ story. He came to Cambridge peddling his wares by horse and wagon. Over the years, he acquired enough capital to lease some property at 315 High Street. There he opened a furniture store and it became one of the largest on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Unfortunately, the entire complex, his home, the storefront and storage shed, were destroyed in a fire in July of 1892. What furniture he could salvage, he later sold at a discount. He announced in the Democrat and News…

M. Nathan informs the public that he is still carrying a good stock of furniture all kinds at his new quarters over Dunn & McCready ‘s. His prices are lower now than ever, as he wishes to reduce stock so as to avoid moving it to his new store when completed. He invites his friends to call and look him over.

Meyer died in 1911, and the furniture business passed to his son, Milford Nathan. Milford was quite an entrepreneur and business man. He expanded the store on High Street, and eventually opened 8 other furniture stores on the Delmarva Peninsula. Milford was also a civic leader. He was chairman of the board for the Cambridge Hospital, and on the board of the Farmers and Merchants National Bank. Upon his death in 1953, his will established the Nathan Foundation as a charitable organization, his final act of goodwill for the Dorchester community. The foundation gained further support from his wife, Estelle, who died in 1980, and his sister, Bertha Nathan, who died in 1983 as they left their share of the Nathan family inheritance to the foundation. The Nathan Foundation is the largest charitable foundation in Dorchester County, and its charitable gifts have totaled well over $3.5 million.

About that time, in 1988, George H.W. Bush accepted the presidential nomination at the Republican National Convention. In his Inaugural address, he spoke of a “thousand points of light.” That “thousand points of light,” became a national incentive to stimulate community involvement in projects that would improve the community and the community’s self-image. In Cambridge, this “thousand points of light” translated to the “Committee of 100,” men and women who would germinate new ideas to promote the city of Cambridge. The “Committee of 100,” comprised of business people, entrepreneurs and visionaries, came up with four projects to improve Cambridge’s self-image and increase tourism: 1) establish the Richardson Maritime Museum, 2) build a replica of the Choptank River Lighthouse at Long Wharf Park, 3) build a visitor’s center at Sailwinds Park, and 4) and have a skipjack dedicated to the Dorchester Community.

Once these projects were agreed upon, each project had to have its own organization committee, separate from the “Committee of 100” to further develop and sustain the project at hand. The Dorchester Skipjack Committee was formed in 1991 as an offshoot of the Committee of 100. The goal of the new committee was to “improve the economy of Dorchester through tourism and preserve the maritime heritage of the City of Cambridge, Maryland, and Dorchester County.” The newly formed Dorchester Skipjack Committee was fortunate to have at the helm an experienced boat builder who could take the idea of a skipjack dedicated to the Dorchester Community and turn it into reality. This man was Harold Ruark.

Harold Ruark spent the greater part of his life designing and building everything from boats to model aircraft with the precision and perfection of a master craftsman. When the “Committee of 100” settled on having a skipjack dedicated to the Dorchester Community, Harold Ruark headed the Dorchester Skipjack Committee and began to look for a suitable skipjack to rescue for the project. He and a group of volunteers, including the famed local shipwright, James (Mr. Jim) Richardson, searched the rivers and marshes around Cambridge and other areas where skipjack captains would tow their deteriorating skipjacks to dissolve in the salt water of the Chesapeake estuaries. Most skipjacks they found were either too deteriorated to refurbish or too expensive to acquire. They did come across one skipjack, the “Flora Price,” in Denton, Maryland, but Harold felt it was too far gone to refurbish. Their mission then transitioned from “finding, buying, and refitting” an aging skipjack to building a new skipjack for the Dorchester Community.

The mission of the Dorchester Skipjack Committee was to document and preserve the skills and knowledge of building and operating these unique commercial sailing vessels before their heritage was lost. At that time, it has been nearly 40 years since a working skipjack was built on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay. Harold Ruark drew up plans for the skipjack. This was the only skipjack ever built from documented plans and drawings. Skipjacks were generally built in the backyard of the captain, using the height of suitable loblolly pine trees to determine the length and width of the boat. Harold modeled the new skipjack on a previously owned family skipjack, the Oregon, and blended in features from other skipjacks, such as the Martha Lewis and the Lady Katie. He also designed the pushboat and carved the beautiful trailboards and eagle figurehead.

When it came time to fund the skipjack project, the Dorchester Skipjack Committee turned to the Nathan Foundation. The foundation, while retaining the memory of Meyer Nathan, was established through the will of his son, Milford Nathan, in 1963. The foundation agreed to fund the project for $25,000 for each of three (3) years, with three stipulations: 1) the project had to be owned by an entity entirely separate from the Committee of 100, 2) the name “Nathan” had to appear in the title; and 3) a member of the Nathan Board had to sit on the Skipjack Board. When the project was well underway, a meeting was held to decide the name of the boat. The skipjack was to be called, “The Nathan of Dorchester”. Thus Meyer Nathan found his place in the history of the skipjack in Dorchester County that bears his family name.